CCUS and upstream projects - The cost of "doing the right thing"

(Originally posted in June 12, 2024)

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is becoming a key consideration for reducing the scope 1 & 2 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of an upstream oil and gas project. However, introducing CCS to a project comes with additional cost and we have to consider who will pay for this. I am not looking to make any criticism of CCS as a solution to reduce emissions for an upstream project, simply asking the question "who pays?".

CCS is of particular interest in Asia-Pacific, where we have a number of undeveloped gas fields that have high levels of formation CO2 (see the next section for why this is important). In this article, I am going to look at the economic impact of including CCS in an upstream project. I could have picked a number of projects for this, but will use an asset for which I have already published other analysis, namely the Abadi field in Indonesia.

Emissions sources in upstream projects

For a typical upstream field development, we can consider four main sources of scope 1 & 2 greenhouse gas emissions:

- Fuel combustion: emissions from burning fuel gas, diesel or other combustible fossil fuels at the facilities to generate the power required to operate the facilities. The power requirement can be reduced through careful process and equipment selection however, there will always be some load. This could be met without (direct) emissions through electrification from shore but this won't be an option for Abadi where the distance and lack of renewables generation on shore makes this impractical.

- Flaring: the (non-routine) flaring of the hydrocarbon fluids for process safety reasons. Routine flaring of gas is rarely seen in new field developments these days due to the inherent value of the gas and the recognition that it is not a sound environmental solution. Whilst facilities can be designed to minimise the incidences of non-routine flaring, there will aways be some situations where this is a requirement.

- Fugitive emissions: releases of greenhouse gasses through equipment leaks, defective seals or joints. Again, work can be done minimise these emissions through leak prevention, leak detection and remedial action.

- Formation CO2: carbon dioxide produced with the reservoir fluids that needs to be removed in order to meet the sales specification. Not all reservoirs are created equal in this regard and the CO2 content of the reservoir gas can vary significantly. Here in Asia-Pacific we are prone to higher levels of formation CO2, with many of the larger undeveloped gas fields having significant CO2 content. Abadi gas has a CO2 content of almost 10% and we can find examples of fields with both significantly lower CO2 content (e.g. Scarborough, ~0.1%) and significantly higher CO2 content (e.g. Barossa, ~18%, or Natuna D-Alpha, >70%). For the hydrocarbon gas to be converted to LNG, this CO2 content will need to be reduced to almost zero with a number of established processes in-place.

CO2 "capture"

When it comes to CCS and upstream projects, the focus has very much been on capturing the formation CO2 for fields where this is significant. The main reason for this is that it is the easiest to capture, in that the CO2 already has to be removed (captured) from the hydrocarbon stream in order to meet the sales specification. This waste (CO2-rich) stream would typically be flared/vented but, after some minimal further treatment as well as compression/pumping, can be injected into a reservoir or aquifer for storage. To "capture" CO2 from any of the three other sources above would require significant additional expense.

One thing we have to remember about the application of CCS for the capture and storage of formation CO2 to a major gas-to-LNG project such as Abadi, Gorgon or Barossa, is that that the produced LNG will still only be of comparable "emissions intensity" to LNG produced from a project based on developing a gas field with low CO2 e.g. the Scarborough / Pluto T2 project in Western Australia.

CCS and Abadi

An outline of the Abadi field development, as published by INPEX, is shown below. The development is based on subsea wells and an FPSO, with a gas export pipeline (GEP) taking the production to shore, where the gas will feed into a new onshore LNG liquefaction plant.

In December 2023, a modified Plan of Development (PoD) was approved for the Abadi field, with one of the big modifications being the inclusion of CCS. As a a part of this approval, it was confirmed that the costs associated with CCS will be cost recoverable. Full details of the CCS inclusions have not been provided but my assumption is that it will focus on the FPSO, with the bulk of the (~10%) formation CO2 removed here. This removed stream will then become the captured CO2 that will be treated, compressed/pumped and re-injected into the Abadi reservoir. Published reports have suggested a cost increase of about US $1.3 billion for the inclusion of CCS, although these costs are from 2022.

Economic modeling

I looked at the economics of the Abadi development (without CCS) last year: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/indonesia-ma-pertamina-petronas-acquire-shells-stake-chambers/ and am using this model as the basis for this analysis.

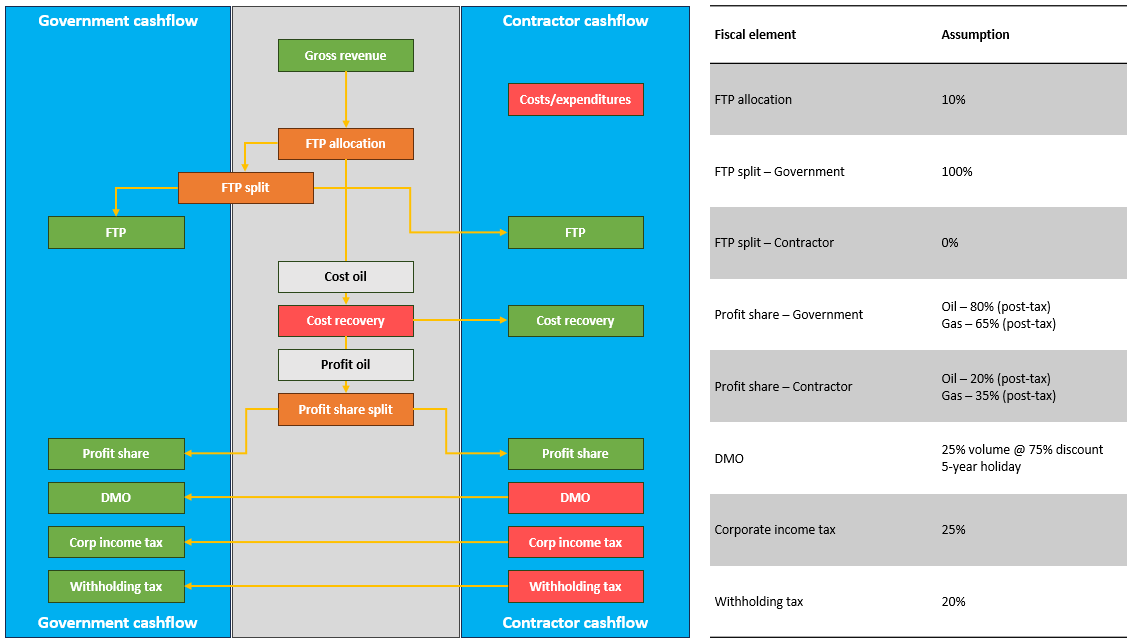

As stated in the previous article, I don't have access to the full details of the Masela PSC and have therefore used model contract terms as the basis of my analysis. An outline of my assumed terms is provided below together with some of the main assumptions.

The inputs for costs and production are as per the previous analysis, with some small adjustments made to update the base year to 2024 and update some of the pricing similarly. In addition, no allowance was made for CCS in my previous analysis.

Where I have included CCS, I have assumed an additional upfront CAPEX of US $1.5 billion for the inclusion of CCS (a bit higher than the reported US $1.3 billion) together with some increase in OPEX.

Economic comparison for the inclusion of CCS

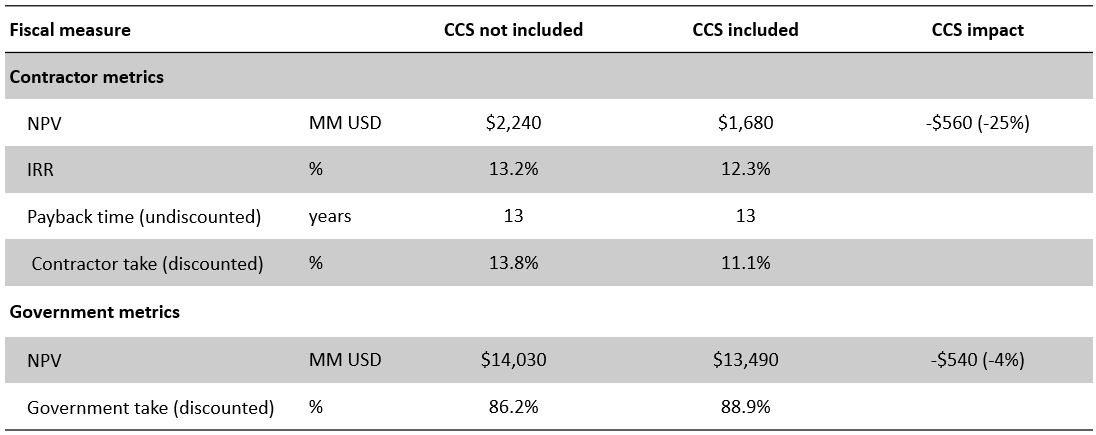

A comparison of some of the key economic metrics based on the inclusion or exclusion of CCS is shown below. To simplify the comparison, all of the below valuations are based on the estimated economic life of the asset (to 2067) rather than the current expiry of the Masela PSC (to 2055).

From this analysis, it can be seen that including CCS within the Abadi field development has a tangible impact on the cash flows of both the contractors (currently INPEX, Pertamina and PETRONAS Carigali) and the Indonesian government. In dollar terms, both parties take a pretty similar hit but, if you consider it as a percentage of NPV, then the contractor takes a significantly bigger cut.

Mitigating the loss in value for including CCS

This leads to the question: "Can this value impact be mitigated?". The simple answer here is not for all parties. By including CCS, we are spending more money and this will have to come from somewhere. However, there are a number of options that could be considered to encourage the application of CCS for the project.

Option 1: make the contractors whole

For the contractors to invest in the project, it will need to meet their economic hurdles and be competitive against other opportunities across their portfolio. To motivate the contractors to include CCS, the government may need allow the contractor to make the same returns for the project regardless of the inclusion of CCS to allow the project to proceed. This is easily done by some tweaks to the fiscal terms, with the most obvious one in this case being the profit split. From some quick analysis, the contractor profit split for gas would need to be increased from 35% to 39.5% to deliver the same returns.

Doing this means that the government is essentially taking the hit. This is no different to say introducing specific terms to incentivise investment into a desired opportunity set, e.g. deepwater.

Option 2: Carbon tax

A well designed carbon tax (a tax on greenhouse gas emissions) would make CCS the logical development solution for the project i.e. due to the carbon tax, the economics of including CCS are better than the economics of not including CCS.

I have done some simple calculations, based on the assumption that the carbon tax would be applied to the bottom line (i.e. after the withholding tax), to estimate the required carbon tax that would give an equivalent return for the inclusion or exclusion of CCS. From my calculations, this is about US $40/tonne. Given the inclusion of the tax removes cashflow from the contractors, the government may need to give back through fiscal term adjustments (as per option 1) to ensure the project is viable.

Whilst there are a lot of countries looking at a carbon tax, it creates a competitiveness challenge if it is not applied universally and consistently between countries.

Option 3: Carbon credits

I don't have the highest opinion of carbon credits as a whole but, putting this to one side, if carbon credits were issued for the emissions prevented through the application of CCS then, provided the value of these were sufficient (i.e. the US $40/tonne as per above), it would make including CCS the logical economic option.

Whilst I can see the justification for issuing carbon credits for CCS projects that capture current sources of emissions (e.g. Santos' Moomba CCS project in Australia) I struggle with justifying the issuing of carbon credits for emissions that are only being issued to support the development of the very project that is producing these emissions.

Option 4: External support / funding

By this, I mean support or funding from another government or international organisation. For Abadi, there are two potential options.

The first can be ringfenced around INPEX where, if my understanding is correct, INPEX are lobbying to get some form or credit / support from the Japanese government for the CCS element of the project. The Japanese government have shown an interest in assisting Japanese companies when it comes to abating overseas emissions or exporting CO2 from Japan for storage elsewhere. However, I would again question the justification of support / funding for emissions that support the development of the very project that will generate said emissions. It also creates some interesting conversations with the other project partners (Pertamina and PETRONAS) about the distribution of such support.

An alternative would be to get funding from an international organisation such as the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP). However, I see this as a bit of a dead-end as they would be unlikely to provide financial support for a new oil and gas project.

Option 5: Markets create pricing based on "Carbon intensity"

It wasn't so long ago that the companies were falling over each other to announce "carbon neutral" cargoes of both LNG and oil. However, the energy trilemma pendulum has swung firmly away from sustainability and towards security and affordability, resulting in buyers no longer being willing to pay premiums for these cargoes.

As LNG markets start to head back towards over-supply, we may see these "luxury" ideals come back and price differentials emerge based on the carbon intensity of an LNG cargo. From my calculations, a discount of about 1% on the slope assumed on the LNG price would result in a project with CCS (achieving a 12.5% slope) giving better returns than a project without CCS (achieving a 11.5% slope).

Conclusions and comments

The unfortunate reality for our region is that a disproportionate percentage of our larger undeveloped gas fields have a high level of formation CO2. Whilst leaving this gas in the ground is always an option, we are likely going to need to develop some of them to address all three pillars of the energy trilemma. Domestic gas production improves the security of supply and energy affordability, as well as providing an important bridge fuel during the transition from coal to whatever the future may hold.

The application of CCS to these field developments is backed by good intentions to reduce emissions. However, it costs money and either the government or the contractors will need to carry these costs.